Leonidas and Xerxes Led Their Armies in Similar Fashions

Thermopylae is a mountain pass near the ocean in northern Greece which was the site of several battles in artifact, the most famous being that between Persians and Greeks in August 480 BCE. Despite beingness greatly junior in numbers, the Greeks held the narrow laissez passer for three days with Spartan rex Leonidas fighting a last-ditch defence with a small force of Spartans and other Greek hoplites. Ultimately the Persians took control of the laissez passer, but the heroic defeat of Leonidas would assume legendary proportions for later generations of Greeks, and within a year the Persian invasion would be repulsed at the battles of Salamis and Plataea.

Context: The Persian Wars

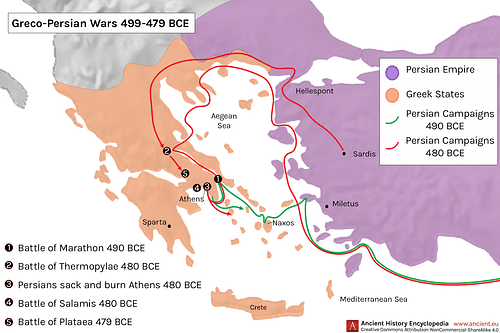

Past the first years of the 5th century BCE, the Persian Achaemenid Empire, nether the rule of Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE), was already expanding into mainland Europe and had subjugated Thrace and Macedonia. Next in Rex Darius' sights were Athens and the rest of Hellenic republic. Just why Greece was coveted by Persia is unclear. Wealth and resources seem an unlikely motive; other more plausible suggestions include the need to increment the prestige of the king at home or to quell once and for all a collection of potentially troublesome insubordinate states on the western border of the empire.

Whatever the exact motives, in 491 BCE Darius sent envoys to call for the Greeks' submission to Persian rule. The Greeks sent a no-nonsense reply by executing the envoys, and Athens and Sparta promised to form an alliance for the defence of Greece. Darius' response to this diplomatic outrage was to launch a naval force of 600 ships and 25,000 men to assail the Cyclades and Euboea, leaving the Persians only one step away from the rest of Greece. In 490 BCE Greek forces led by Athens met the Persians in battle at Marathon and defeated the invaders. The battle would take on mythical condition amid the Greeks, merely in reality information technology was but the opening overture of a long war with several other battles making up the principal acts. Persia, with the largest empire in the world, was vastly superior in men and resources and now these would be fully utilised for a full-scale attack.

Greco-Farsi Wars

In 486 BCE, Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) became king upon the decease of Darius and massive preparations for invasion were made. Depots of equipment and supplies were laid, a culvert dug at Chalkidike, and boat bridges built beyond the Hellespont to facilitate the motion of troops. Greece was nearly to face its greatest always threat, and fifty-fifty the oracle at Delphi ominously advised the Athenians to 'wing to the globe's terminate'.

The Laissez passer of Thermopylae

When news of the invading force reached Greece, the initial Greek reaction was to send a strength of 10,000 hoplites to hold position at the valley of Tempē near Mt. Olympos, merely these withdrew when the massive size of the invading regular army was revealed. Then afterwards much discussion and compromise betwixt Greek city-states, suspicious of each others' motives, a joint army of between 6,000 and 7,000 men was sent to defend the pass at Thermopylae through which the Persians must enter mainland Greece. The Greek forces included 300 Spartans and their helots with two,120 Arcadians, 1,000 Lokrians, 1,000 Phokians, 700 Thespians, 400 Corinthians, 400 Thebans, 200 men from Phleious, and 80 Mycenaeans.

Thermopylae was an fantabulous choice for defence with mountains running downwardly into the ocean leaving only a narrow pass along the declension.

The relatively small size of the defending forcefulness has been explained equally a reluctance past some Greek city-states to commit troops then far n, and/or due to religious motives, for it was the flow of the sacred games at Olympia and the virtually of import Spartan religious festival, the Karneia, and no fighting was permitted during these events. Indeed, for this very reason, the Spartans had arrived too belatedly at the earlier Battle of Marathon. Therefore, the Spartans, widely credited equally being the best fighters in Greece and the only polis with a professional person army, contributed just a small advance strength of 300 hoplites (from an estimated eight,000 bachelor) to the Greek defensive force, these few existence chosen from men with male person heirs.

In addition to the country forces, the Greek poleis sent a fleet of trireme warships which held position off the coast of Artemision (or Artemisium) on the northern coast of Euboea, 40 nautical miles from Thermopylae. The Greeks would aggregate over 300 triremes and perhaps their principal purpose was to prevent the Persian fleet sailing down the inland declension of Lokris and Boeotia.

Greek Hoplite

The pass of Thermopylae, located 150 km north of Athens was an excellent pick for defence with steep mountains running downwardly into the sea leaving only a narrow marshy expanse forth the coast. The pass had also been fortified by the local Phokians who congenital a defensive wall running from the then-called Middle Gate down to the body of water. The wall was in a country of ruin, but the Spartans fabricated the best repairs they could in the circumstances. It was hither, and so, in a 15-metre wide gap with a sheer cliff protecting their left flank and the ocean on their right, that the Greeks chose to make a stand confronting the invading army. Having somewhere in the region of lxxx,000 troops at his disposal, the Persian king, who led the invasion in person, first waited four days in expectation that the Greeks would flee in panic. When the Greeks held their position, Xerxes one time again sent envoys to offer the defenders a last adventure to surrender without bloodshed if the Greeks would only lay down their artillery. Leonidas' bullish response to Xerxes request was 'molōn labe' or 'come and become them' and so battle commenced.

Hoplites vs Archers

The two opposing armies were essentially representative of the ii approaches to Classical warfare - Farsi warfare favoured long-range assault using archers followed upwards with a cavalry charge, whilst the Greeks favoured heavily-armoured hoplites, bundled in a densely packed germination called the phalanx, with each homo carrying a heavy round statuary shield and fighting at close quarters using spears and swords. The Farsi infantry carried a lightweight (oftentimes crescent-shaped) wicker shield and were armed with a long dagger or battleaxe, a short spear, and composite bow. The Persian forces also included the Immortals, an elite force of 10,000 who were probably better protected with armour and armed with spears. The Persian cavalry were armed as the foot soldiers, with a bow and an boosted two javelins for throwing and thrusting. Cavalry, usually operating on the flanks of the principal battle, were used to mop upwardly opposing infantry put in disarray later on they had been subjected to repeated salvos from the archers. Although the Persians had enjoyed the upper hand in previous contests during the contempo Ionian defection, the terrain at Thermopylae would improve arrange Greek warfare.

Persian Archers

Although the Persian tactic of rapidly firing vast numbers of arrows into the enemy must accept been an crawly sight, the lightness of the arrows meant that they were largely ineffective against the statuary-armoured hoplites. Indeed, Spartan indifference is epitomised by Dieneces, who, when told that the Persian arrows would be so dense as to darken the sun, replied that in that instance the Spartans would accept the pleasure of fighting in the shade. At close quarters, the longer spears, heavier swords, better armour, and rigid subject of the phalanx formation meant that the Greek hoplites would have all of the advantages, and in the narrow confines of the terrain, the Persians would struggle to make their vastly superior numbers tell.

Battle

On the first day, Xerxes sent his Median and Kissian troops, and after their failure to clear the laissez passer, the aristocracy Immortals entered the battle but in the brutal close-quarter fighting, the Greeks held firm. The Greek tactic of feigning a disorganised retreat and then turning on the enemy in the phalanx formation likewise worked well, lessening the threat from Farsi arrows and perhaps the hoplites surprised the Persians with their disciplined mobility, a benefit of being a professionally trained ground forces.

The second day followed the pattern of the get-go, and the Greek forces even so held the laissez passer. However, an unscrupulous traitor was nearly to tip the balance in favour of the invaders. Ephialtes, son of Eurydemos, a local shepherd from Trachis, seeking reward from Xerxes, informed the Persians of an alternative route —the Anopaia path— which would allow them to avert the majority of the enemy forces and attack their southern flank. Leonidas had stationed the contingent of Phokian troops to guard this vital point but they, thinking themselves the primary target of this new development, withdrew to a higher defensive position when the Immortals attacked. This suited the Persians every bit they could now continue unimpeded along the mount path and get in behind the main Greek strength. With their position at present seemingly hopeless, and earlier their retreat was cut off completely, the bulk of the Greek forces were ordered to withdraw by Leonidas.

Leonidas

Concluding Stand

The Spartan king, on the third mean solar day of the boxing, rallied his small-scale forcefulness - the survivors from the original Spartan 300, 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans - and made a rearguard stand to defend the laissez passer to the last man in the promise of delaying the Persians progress, in lodge to allow the balance of the Greek strength to retreat or likewise perchance to await relief from a larger Greek force. Early in the morning, the hoplites one time more than met the enemy, simply this fourth dimension Xerxes could attack from both forepart and rear and planned to practice so but, in the event, the Immortals behind the Greeks were belatedly on arrival. Leonidas moved his troops to the widest part of the laissez passer to utilize all of his men at once, and in the ensuing clash the Spartan king was killed. His comrades then fought fiercely to recover the body of the fallen king. Meanwhile, the Immortals at present entered the fray backside the Greeks who retreated to a high mound backside the Phokian wall. Perhaps at this bespeak the Theban contingent may accept surrendered (although this is disputed amid scholars). The remaining hoplites, now trapped and without their inspirational king, were subjected to a barrage of Western farsi arrows until no human being was left standing. After the battle, Xerxes ordered that Leonidas' head be put on a stake and displayed at the battlefield. Every bit Herodotus claims in his business relationship of the battle in book Vii of The Histories, the Oracle at Delphi had been proved right when she proclaimed that either Sparta or 1 of her kings must fall.

Meanwhile at Artemision, the Persians were battling the elements rather than the Greeks, as they lost 400 triremes in a tempest off the coast of Magnesia and more in a second tempest off Euboea. When the two fleets finally met, the Greeks fought late in the day and therefore limited the elapsing of each skirmish which diminished the numerical advantage held by the Persians. The result of the boxing was, notwithstanding, indecisive and on news of Leonidas' defeat, the fleet withdrew to Salamis.

The Aftermath

The battle of Thermopylae, and specially the Spartans' role in it, soon acquired mythical condition amongst the Greeks. Free men, in respect of their ain laws, had sacrificed themselves in club to defend their way of life against foreign aggression. As Simonedes' epitaph at the site of the fallen stated: 'Get tell the Spartans, y'all who read: We took their orders and here lie dead'.

A glorious defeat possibly, but the fact remained that the way was at present clear for Xerxes to push on into mainland Greece. The Greeks, though, were far from finished, and despite many states now turning over to the Persians and Athens itself being sacked, a Greek army led by Leonidas' brother Kleombrotos began to build a defensive wall near Corinth. Wintertime halted the country campaign, though, and at Salamis the Greek fleet manoeuvred the Persians into shallow waters and won a resounding victory. Xerxes returned home to his palace at Sousa and left the gifted general Mardonius in charge of the invasion. Later on a series of political negotiations information technology became clear that the Persians would not gain victory through affairs and the 2 armies met at Plataea in August 479 BCE. The Greeks, fielding the largest hoplite army always seen, won the battle and finally ended Xerxes' ambitions in Greece.

As an interesting footnote: the of import strategic position of Thermopylae meant that it was once more the scene of battle in 279 BCE when the Greeks faced invading Gauls, in 191 BCE when a Roman ground forces defeated Antiochus Iii, and even as recent every bit 1941 CE when Centrolineal New Zealand forces clashed with those of Germany.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to bookish standards prior to publication.

0 Response to "Leonidas and Xerxes Led Their Armies in Similar Fashions"

Post a Comment